Here’s a question: in the climactic moment of The Lord of the Rings, who was responsible for the Ring’s destruction? Was it Frodo? Gollum? Maybe Sam? Alternatively, was it Eru? Is there a sense in which we could say it was Sauron, or even the Ring, itself?

There’s a reading of the climax of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings that takes a strong stance on the answer to the above questions. It’s a reading that has floated around fan spaces since at least the mid 2000s. Put simply it states that Gollum’s Ring-destroying fall into the Cracks of Doom as he “danced too close to the edge” was not directly caused by his careless dancing, but rather was the result of him being “pushed” or “tripped” by Eru, Tolkien’s Creator-God. The argument for this reading appears to be centered on the contents of a letter Tolkien addressed to Amy Ronald in July of 1956 (hereafter referred to per its designation in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien as Letter 192). In it Tolkien explains that the climax at the Cracks of Doom represents a time in the story where “the Other Power took over,” completing the task that Frodo was incapable of completing on his own (Tolkien, Letters 252). The “tripped” interpretation of this moment appears to assign to Tolkien’s statement in Letter 192 the meaning that Gollum was made to fall by a singular, direct, unilateral act of Eru—that is: divine intervention—a literal deus ex machina as the “finger of God” intruded into history. This reading of Letter 192 is prominent enough in fan consciousness that as of this writing, even the entry for “Eru Ilúvatar” on One Wiki to Rule Them All lists it alongside The Drowning of Numenor as one of four moments in the history of Middle-earth when Eru actively and miraculously intervened (“Involvement”), an association that is significant for reasons which will soon become clear.

In my usage “con-creation” is the total continuous creative activity (by which I also mean choice-making about mundane things) of all creatures capable of choice, across all time—rather than the creative activity of a set number of said individuals greater than one (“co-creation”)

This reading of the scene, and of the Letter used to argue for it, is highly selective and disregards both the context of said letter and numerous pieces of evidence that suggest contrary readings, both within the text of The Lord of the Rings and outside of it. It also requires mischaracterizing the very present and widely-recognized functioning of Providence in Eä by recasting it instead as miracle. Additionally, if true, it would work to undermine some of the most prominent themes in The Lord of the Rings, including those themes Tolkien, himself, identifies within his letters, damaging the work’s dramatic unity and rendering The Lord of the Rings unsatisfactory from a narrative perspective. Most important for my purposes, I believe that this very unsatisfactory-ness is evidence that this reading cannot be true without running afoul of one of the most important underlying aspects of the metaphysics of Tolkien’s Legendarium—the “story-nature” of Eä.

I will “unweave” this interpretation and then “reweave” the loosened threads of story into a different pattern, one I am calling “con-creation.” In my usage “con-creation” is the total continuous creative activity (by which I also mean choice-making about mundane things) of all creatures capable of choice, across all time—rather than the creative activity of a set number of said individuals greater than one (“co-creation”)—as a means of creating in concert with a Prime Creator who supports the total product of con-creation by supplying it with primary being. It could be likened metaphorically to the production of an improv-heavy play. This idea is so central to The Lord of the Rings in particular and to Tolkien’s Legendarium in total that it—like eucatastrophe—”rends the web of story” (Tolkien, Tolkien On Fairy-stories 76) and enters into the real world, encompassing the reader as well.

Part One: Catching the Snag

What Does the Text Say?

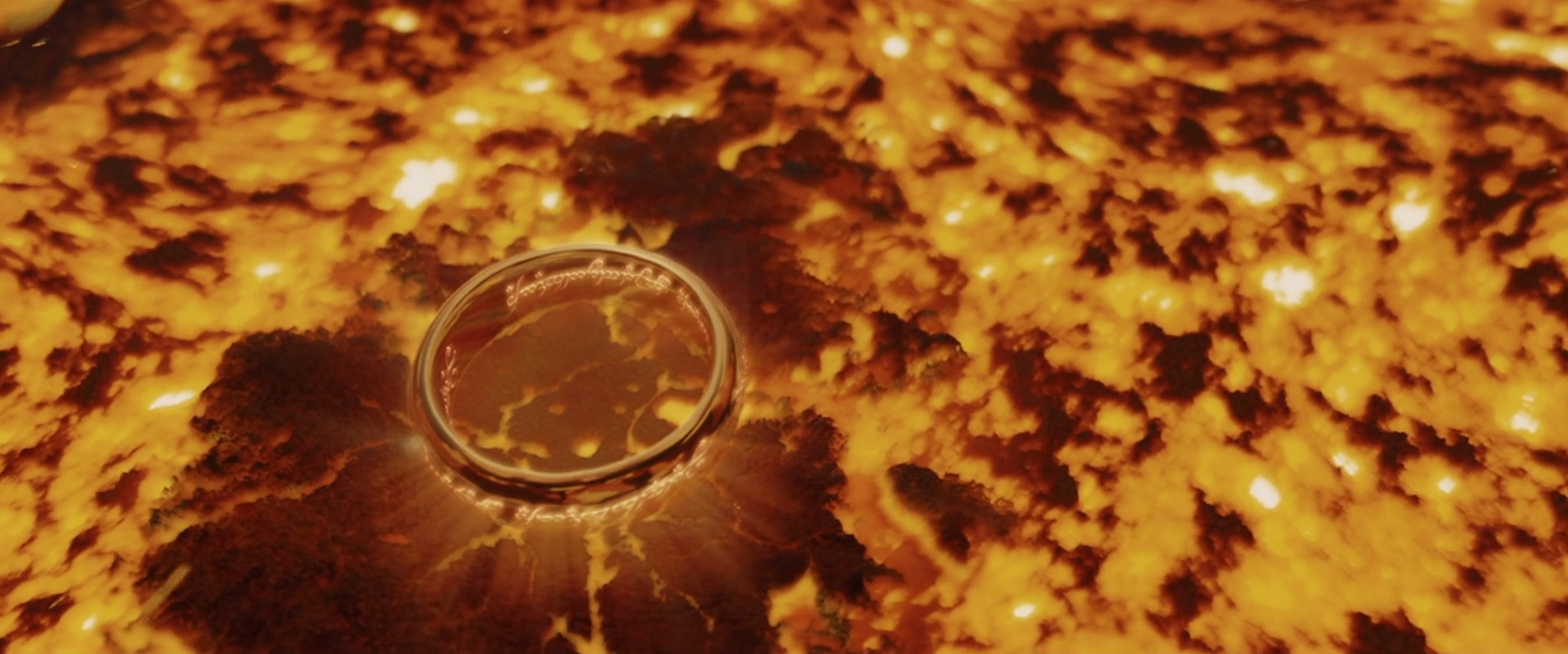

The climax of the quest to destroy the One Ring occurs inside the Cracks of Doom—a fissure opening into the side of the volcano, Mount Doom—where a precipice extends over the pit of magma at the heart of Sauron’s domain. It is here that the Ring was forged and here and only here that it can be destroyed.

During the climactic scene Frodo is overcome by the temptation of the Ring’s constant enticement, and instead of throwing the Ring into the magma he claims it for himself and slides it on his finger, disappearing from view as it renders him invisible. Shortly thereafter, Sam is knocked momentarily unconscious by Gollum who jumps on the invisible Frodo and fights him for possession of the Ring.

The scene that describes what happens next—Gollum’s fall and the Ring’s final moments—is extremely short, lasting only three paragraphs near the end of the Chapter ‘Mount Doom.’ It is told from Sam’s perspective:

Sam got up. He was dazed, and blood streaming from his head dripped in his eyes. He groped forward, and then he saw a strange and terrible thing. Gollum on the edge of the abyss was fighting like a mad thing with an unseen foe. To and fro he swayed, now so near the brink that almost he tumbled in, now dragging back, falling to the ground, rising, and falling again. And all the while he hissed but spoke no words.

The fires below awoke in anger, the red light blazed, and all the cavern was filled with a great glare and heat. Suddenly Sam saw Gollum’s long hands draw upwards to his mouth; his white fangs gleamed, and then snapped as they bit. Frodo gave a cry, and there he was, fallen upon his knees at the chasm’s edge. But Gollum, dancing like a mad thing, held aloft the ring, a finger still thrust within its circle. It shone now as if verily it was wrought of living fire.

‘Precious, precious, precious!’ Gollum cried. ‘My Precious! O my Precious!’ And with that, even as his eyes were lifted up to gloat on his prize, he stepped too far, toppled, wavered for a moment on the brink, and then with a shriek he fell.

Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings 946

The action here seems quite clear: in the first paragraph we are told that Gollum is “on the edge of the abyss” and is fighting an invisible adversary “so near the brink that he almost tumbled in.” The action is set up and the outcome foreshadowed.

In the second paragraph Frodo suddenly becomes visible at “the chasm’s edge” as Gollum bites off his finger, detaching the ring from Frodo’s body. Gollum is then described as “dancing like a mad thing,” and holding the ring “aloft.” Gollum has seemingly triumphed and is ecstatic.

In the third paragraph we are told that two things happen at once: Gollum’s eyes “lifted up to gloat on his prize” while at the same time he “stepped too far, toppled, wavered for a moment on the brink” and then fell off the edge.

Gollum was staring at the Ring, raised in gloating exultation into the air, while dancing in triumph right next to the edge of a chasm. Quite simply: Gollum wasn’t looking where he was going. In his mad glee at having once again reclaimed the object that has devoured him mind, body, and soul with boundless hateful love for over five hundred years, he had no care for his own physical safety, leading him to fall to his death, taking the Ring (accidentally? coincidentally?) with him. This fate is clearly foreshadowed in the first two paragraphs where we are told three times before the event happens that he and Frodo are both dangerously close to the edge.

With only this scene to go on, we may say this issue is extremely straightforward. So what does Letter 192 have to say about it?

The “Tripped” Argument

Letter 192 is one of a number of letters wherein Tolkien, responding to a reader, addresses the question of Frodo’s failure: that is, his failure to throw the Ring into the magma deep inside the Cracks of Doom, destroying it and ending the threat of Sauron’s dominion over Middle-earth. In the letter Tolkien states the inevitability of Frodo’s failure and then addresses the forces that lead to the completion of the quest in his stead:

Frodo deserved all honour because he spent every drop of his power of will and body, and that was just sufficient to bring him to the destined point, and no further. Few others, possibly no others of his time, would have got so far. The Other Power then took over: the Writer of the Story (by which I do not mean myself) ‘that one ever-present Person who is never absent and never named’ (as one critic has said).

Letters 252

The last sentence—Tolkien’s admission that the cause was completed by “The Other Power”/“The Writer of the Story”—is the primary evidence cited in defense of the “tripped” reading. Another reference to the “Writer of the Story” in the same context appears in a letter drafted by Tolkien just the day before. The topic is the same: Frodo’s failure and the completion of the quest in his stead:

I did not ‘arrange’ the deliverance in this case: it again follows the logic of the story. (Gollum had had his chance of repentance, and of returning generosity with love; and had fallen off the knife-edge.) (…) But one must face the fact: the power of Evil in the world is not finally resistible by incarnate creatures, however ‘good’; and the Writer of the Story is not one of us.

251

I will quote the summary of the “tripped” interpretation of these letters from the “Eru Iluvatar” article One Wiki to Rule Them All: “J.R.R. Tolkien stated in a letter that Eru again intervened at the end of the Third Age, causing Gollum to trip and fall into the fires of Mount Doom while holding the One Ring, thus destroying it” (“Involvement”).

Two things about the “tripped” interpretation are thus clear: Eru (understood as “The Writer of the Story”) “intervened,” and this intervention consisted of “causing Gollum to trip and fall.” This is a singular, direct, and unilateral action: “singular” because it is a unique act of Eru in this particular circumstance meant to cause a specific and distinct change in the world without respect to other causes, “direct” because Eru is its direct cause, and “unilateral” in that Eru accomplishes this without regard to the actions or wills of any other rational being.

Two things about the “tripped” interpretation are thus clear: Eru (understood as “The Writer of the Story”) “intervened,” and this intervention consisted of “causing Gollum to trip and fall.” This is a singular, direct, and unilateral action: “singular” because it is a unique act of Eru in this particular circumstance meant to cause a specific and distinct change in the world without respect to other causes, “direct” because Eru is its direct cause, and “unilateral” in that Eru accomplishes this without regard to the actions or wills of any other rational being.

In the same article on One Wiki to Rule Them All, three other examples of Eru’s intervention are given: the awakenings of Elves and Men—that is, the creation of human beings as rational, independent creatures—and the Drowning of Numenor, when Eru reshaped Arda (the world) into a sphere near the end of the Second Age (“Involvement”). All of these examples also represent singular, direct, and unilateral actions; additionally, they are actions which would be either forbidden or physically and metaphysically impossible for any other beings that exist in Eä (the universe). For example, the creation of an entire race of “rational beings” is something we are told point blank that only Eru can accomplish (indeed this is the “moral” of the story of the creation of the Dwarves); likewise the complete physical restructuring of the entire planet and (presumably) all the changes to the laws of nature that would be required by such an action appear to be well outside the bounds of what the Aniur (Tolkien’s pantheon of demiurgic angel-gods) are both allowed to do and are capable of doing. Indeed, so singular, direct, and unilateral is the Drowning of Numenor as a world event within the greater scope of the course of history, that Tolkien explicitly refers to it as a “change of plan” (Letters 205).

According to Richard Purtill in J.R.R. Tolkien: Myth, Morality, and Religion, this reshaping of Arda can be said to constitute “a miracle in the strongest sense: it was a direct intervention of God into the world in such a way that normal physical laws and processes were suspended” (154). If we accept Purtill’s characterization of miracle, it would appear then that the “tripped” interpretation requires that the Ring was only destroyed because of a miraculous intervention by Eru, a type of intervention otherwise characterized in events (of larger scale but of the same type) such as the Drowning of Numenor. Put another way, Eru literally caused a change in the material determinism of Arda such that Gollum tripped in order to destroy the Ring when Frodo failed to do so.

Do the relevant texts actually support Gollum’s fate as the result of a miracle—a singular, direct, and unilateral action on the part of Eru? Does it make sense for Eru, from what we know of him from the rest of Tolkien’s work and from the underlying metaphysics of Ea, to function in this way in such a situation? Did Eru literally trip Gollum in order to complete the quest Frodo had failed? Before I examine this question further, I want to explore another proposed interpretation of Gollum’s consequential “fall” because I believe it will shed light on why a gentler handling of the causal mechanisms at work in the climax of The Lord of the Rings better reveals the event’s narrative subtleties and thematic (and theological and metaphysical) importance.

Part 2: Untangling the Knots

An Alternate Argument

An alternative explanation for Gollum’s fall also attempts to describe it as the direct work of a singular force: a curse placed on him. Evidence for this explanation comes in the form of three exchanges between Frodo and Gollum which essentially bookend their time together over the course of the novel. The first occurs not long after Gollum has accosted Frodo and Sam as they journey towards Mordor. Sam has tied an elven rope around Gollum’s leg as a kind of makeshift leash; desperate to be rid of the rope, Gollum pleads for his release and promises to swear on the Precious (the Ring) to do Frodo and Sam no harm if they will release him. Frodo tries to impress on Gollum that swearing on (or by) the Precious is a dangerous proposition:

‘On the Precious? How dare you?’ [Frodo] said. ‘Think!

One Ring to rule them all and in the Darkness bind them.

Would you commit your promise to that, Sméagol? It will hold you. But it is more treacherous than you are. It may twist your words. Beware!’Gollum cowered. ‘On the Precious, on the Precious!’ he repeated.

Tolkien, Lord of the Rings 617

Eventually Gollum does swear to “serve the master of the Precious” (618), and this oath is recalled two chapters later when Frodo again attempts to impress upon Gollum the great danger the oath has put him in. Frodo reminds Gollum that the Ring will work to twist Gollum’s oath against him, due in part to the incredible hold over him that it already has. Frodo contrasts his own relative lack of temptation from the Ring with that of Gollum:

‘In the last need, Sméagol, I should put on the Precious; and the Precious mastered you long ago. If I, wearing it, were to command you, you would obey, even if it were to leap from a precipice or to cast yourself into the fire. And such would be my command. So have a care, Sméagol!’

640

Similar phrasing will appear again in the last confrontation between Gollum and Frodo before the climactic events at the Cracks of Doom, when Gollum attacks Frodo as Frodo and Sam are climbing Mount Doom, just a short distance away from where the Ring can be destroyed:

‘Down, down!’ [Frodo] gasped, clutching his hand to his breast, so that beneath the cover of his leather shirt he clasped the Ring. ‘Down, you creeping thing, and out of my path! Your time is at an end. You cannot betray me or slay me now.’

Then suddenly, as before under the eaves of the Emyn Muil, Sam saw these two rivals with other vision. A crouching shape, scarcely more than the shadow of a living thing, a creature now wholly ruined and defeated, yet filled with a hideous lust and rage; and before it stood stern, untouchable now by pity, a figure robed in white, but at its breast it held a wheel of fire. Out of the fire there spoke a commanding voice.

‘Begone, and trouble me no more! If you touch me ever again, you shall be cast yourself into the Fire of Doom.’

943

Certainly, this seems terribly prescient! Gollum does touch Frodo again when he wrestles with him and bites off his finger, and almost immediately afterwards he indeed falls into the Fire of Doom. Is there some mechanism at work here, an active cause? Is he “cast” into the fire just as Frodo said he would be?

The Question of a Curse

Curses (here taken to mean the act of speaking words which invoke a real conditional or unconditional effect on the self or another person) appear throughout Tolkien’s Legendarium. The most famous curse in The Lord of the Rings is likely the curse placed on The Dead Men of Dunharrow by Isildur in response to the breaking of their oath to support him during the Last Alliance against Sauron. Other famous curses in the Legendarium include the curse of Morgoth upon Hurin and his family as well as the Doom of Mandos uttered in response to the Oath of Feanor. A full examination of curses in Arda is far outside the scope of this essay, and their nature—for example, whether they describe individual wills having a real effect upon themselves or others or whether they are merely foresight of the playing out of consequences—is a topic of much debate. However, if we accept for the moment that Gollum’s fall is the result of a curse then the next question is: when was Gollum cursed?

The two most likely options seem to be the following: either Gollum curses himself by swearing an oath to “serve the master of the Precious” and then breaking that oath at the Cracks of Doom, or Gollum is cursed on the slopes of Mount Doom when he fights with Frodo and Sam hears a voice issuing from “the wheel of fire.” In either case the curse activates at such a time as to lead to the coincidentally fortuitous destruction of the Ring along with Gollum.

Let’s further accept (for the moment) that the latter option is the true one. Who then, on the slopes of Mount Doom, is actually doing the cursing? Is it Frodo? Is it Eru? Is it the Ring, itself? It is Frodo who initially speaks, but the voice that speaks the line in question, “you shall be cast,” is coming from out of the Ring. Could it be the Ring doing the cursing?

While I would argue that the Ring is characterized as having some amount of agency1, we do not see the Ring affect others without command or participation on the part of the wielder in such a direct way (nor do we see it able to speak, though it’s possible the latter is part and parcel of the heightened and theatrical mode of the action as seen through Sam’s eyes). Indeed, we do not see the Ring do anything other than make certain wearers invisible and exert its seductive pull. There is the historical suggestion that it is able to change size at will and make certain decisions about its own fate (falling off Isildur’s hand, leaving Gollum), but that the Ring could curse a being without direction from another will seems unlikely. Which leaves us with Frodo. So is it Frodo actively using the Ring to curse Gollum? There are several factors that suggest it is not, both as regards the mechanics of the plot as well as the themes of the story. I will focus on the former for now.

Frodo’s use of the Ring throughout the novel has been passive: he has either clutched it or placed it upon his finger in order to make use of the invisibility it grants. The last time he did the latter was on Amon Hen, where he recognized that wearing the Ring put him in danger of being seen by the roving Eye of Sauron2 and so chose to take it off. While the details of the functioning of the Ring are not spelled out anywhere by Tolkien, who wisely leaves the mechanics of its use to speculation, there is a clear sense that what I will be calling “active use” of the Ring (using it to compel objects or persons in accordance with the wielder’s will) has certain requirements. Back in Lothlorien, after Galadriel rejects Frodo’s offer of the Ring, Frodo asks her about the Ring’s use, and why it was that he had not been able to see the thoughts of others by wearing it:

‘You have not tried,’ she said. ‘Only thrice have you set the Ring upon your finger since you knew what you possessed. Do not try! It would destroy you. Did not Gandalf tell you that the rings give power according to the measure of each possessor? Before you could use that power you would need to become far stronger, and to train your will to the domination of others.’

366

From this we might argue that the kind of active use of the Ring that seems necessary for, say, cursing someone, would require at least three things: for the user to be wearing the Ring, for them to have some intention toward domination, and for them to have some practice in its use in this way. Frodo, however, is not wearing the Ring while on the slope of Mount Doom, and will not wear it until he enters the Cracks of Doom and claims it for his own.3 Neither have we seen him practice use of the Ring for domination. Whether he has the intention of domination in this moment is up for debate, but either way it seems clear that at least two of the apparent prerequisites were not in place for Frodo to have used the Ring in an active way, like “cursing” Gollum such that he was compelled to fall into the fire.4

Still, these three moments are curious, and the question of what they may mean in the context of the narrative remains. It is in their connection to choice and free will on the part of both Frodo and Gollum that I think we will find our ultimate answer, as well as our way back to the thesis at hand: why Eru didn’t trip Gollum. Let’s first look at a better explanation for them.

Prophecies, Prescience, and Foreshadowing

There can be no doubt that these three moments function dramatically as foreshadowing. Tolkien employs foreshadowing frequently, particularly in regards to the circumstances of the climactic scene. In the second chapter of the very first book Gandalf asks Frodo to try “doing away with” the Ring, which Frodo intends to do by hurling it into the fireplace in Bag End; it is a task Frodo fails to do just as he will also fail to do it when it comes time to toss the Ring into the fire in the Cracks of Doom. Additionally, within the context of the logic of the plot and Frodo’s characterization, these three moments may also be examples of Frodo speaking a meaningful threat: Frodo has already told Gollum where they are going and what they plan to do when they get there; the idea that he might throw Gollum in, too, for good measure, seems a reasonable enough threat to make in context—Frodo was initially prepared to kill Gollum after all. Most importantly for our purposes, however, these moments may also be understood as examples of prescience or prophecy.

Like the climactic scene in the Cracks of Doom, the first and final encounters between Frodo and Gollum are both described in part from Sam’s point of view, and in both Sam perceives Frodo dramatically magnified, momentarily larger and more imposing, either filled with hidden light or robed in white:

For a moment it appeared to Sam that his master had grown and Gollum had shrunk: a tall stern shadow, a mighty lord who hid his brightness in grey cloud, and at his feet a little whining dog. Yet the two were in some way akin and not alien: they could reach one another’s minds.

618

Then suddenly, as before under the eaves of the Emyn Muil, Sam saw these two rivals with other vision. A crouching shape, scarcely more than the shadow of a living thing, a creature now wholly ruined and defeated, yet filled with a hideous lust and rage; and before it stood stern, untouchable now by pity, a figure robed in white, but at its breast it held a wheel of fire.

944

We know that Frodo’s time spent as Ring-bearer changed him, honing him spiritually as he struggled long and hard to resist the Ring’s temptation. In “Power and Meaning in The Lord of the Rings,” Patricia Meyer Sparks notes that “in this world as in the Christian one, the result of repeated choices of good is the spiritual growth of the chooser. Frodo’s stature increases markedly in the course of his adventures, and the increase is in the specifically Christian virtues” (61). Back in Lothlorien, Galadriel told Frodo that this process had already begun: “as Ring-bearer and as one that has borne it on finger and seen that which is hidden, your sight is grown keener. You have perceived my thought more clearly than many that are accounted wise” (366).

Like curses, prophecy and foresight—knowledge of the future—appear many times throughout Tolkien’s Legendarium. One of the most well-known examples of prophecy in The Lord of the Rings is that which concerns the fate of the Witch-King of Angmar and is uttered by the reincarnated elf Glorfindel: “Far off yet is his doom, and not by the hand of man will he fall” (1051). Readers know that this is referring to the fact that The Witch-King will be defeated by Eowyn (a woman) and Merry (a hobbit) during the Battle of the Pelennor Fields.

In “Osanwe-kenta,”5 Tolkien’s essay on the nature of what is essentially his Legendarium’s version of “telepathy,” he provides some insight into the metaphysics of foresight in Arda:

[A] mind can learn of the future only from another mind which has seen it. But that means only from Eru ultimately, or mediately from some mind that has seen in Eru some part of His purpose (such as the Ainur who are now the Valar in Eä). (…) But any mind, whether of the Valar or of the Incarnate, may deduce by reason what will or may come to pass. (…)

Minds that have great knowledge of the past, the present, and the nature of Eä may predict with great accuracy, and the nearer the future the clearer (saving always the freedom of Eru).

211

What we know as “foresight” or “prophecy” in Tolkien’s Legendarium then is either knowledge obtained from a source with connections outside of Eä and therefore outside of Time (from one of the Ainur who existed before Eä or from Eru himself) or is a deduction of future events based on the careful examination of the patterns of the present and the past and a knowledge of Eä’s fundamental nature.

Frodo has both grown spiritually (as suggested by his ennobled appearance) to the point that he can better perceive the nature of Eä as well as trends and patterns in the flow of time, and also is privy (to varying degrees and in varying ways) to the knowledge of two maiar: Gandalf—who has shared his suspicions about Gollum’s “role to play” with him—and Sauron—whose being is in a sense incarnate in the Ring hanging around Frodo’s neck.

In The Peoples of Middle-earth, Tolkien compares Glorfindel’s spiritual stature as being on a level of that of the maiar (Tolkien’s lesser order of demiurgic angel-gods) (381). Glorfindel’s time in the Halls of Mandos and his noble death in single combat with a balrog have all contributed to the growth in his spiritual stature. It is possible then that Glorfindel had access to some knowledge of possible futures from the Valar directly or even via revelation directly from Eru by virtue of this spiritual growth. I speculate then that Frodo has both grown spiritually (as suggested by his ennobled appearance) to the point that he can better perceive the nature of Eä as well as trends and patterns in the flow of time, and also is privy (to varying degrees and in varying ways) to the knowledge of two maiar: Gandalf—who has shared his suspicions about Gollum’s “role to play” with him—and Sauron—whose being is in a sense incarnate in the Ring hanging around Frodo’s neck. Indeed, this later fact may go some way to explaining why it is the Ring—“the wheel of fire”—that seems to speak prophecy on the slopes of Mount Doom.

According to Tolkien in Unfinished Tales, Sauron sensed that there was some purpose in Gollum’s continued existence, a sense that prevented him from killing Gollum after torturing him for information on the location of the Ring. In “The Hunt for the Ring” Tolkien relates the strange, indomitable nature of Gollum which Sauron sensed:

[Sauron] did not trust Gollum, for he divined something indomitable in him, which could not be overcome, even by the Shadow of Fear, except by destroying him.

(…) Ultimately indomitable he was, except by death, as Sauron guessed, both from his halfling nature, and from a cause which Sauron did not fully comprehend, being himself consumed by lust for the Ring.

322

If Sauron could sense something about Gollum, then perhaps the Ring, while in Frodo’s possession, could sense it, too. We know Sauron is in rapport with the Ring at all times (Tolkien, Letters 153), whether or not he has it or is aware of its location. It’s possible then that the Ring, itself, “knows” something about Gollum and his future, and that is what is augmenting Frodo in this moment.

One way or another, I believe it makes far more sense to view these moments as examples of prophecy and foresight than curses: in the manner of Glorfindel they foretell an outcome rather than invoke one. Glorfindel did not cause Eowyn and Merry to be able to kill the Witch-king. Likewise, neither Frodo nor the Ring caused Gollum to fall into the fire. But this leads us to our next question: why might a direct, active, intentional or prejudiced “cause” for Gollum’s fall be desired in a reading of the text? And if there isn’t one, does that mean what led to the destruction of the Ring was simply an accident?

Part 3: Examining the Threads

Active and Passive

Both of the interpretations of the book’s climax we have explored thus far reframe what appears upon first reading in the text to be a passive event (Gollum falling by accident due to misstepping) into an active one (Gollum being tripped or compelled to fall). Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Return of the King likewise reframes (or perhaps transforms) the climactic scene. In the film Gollum’s fall is not presented as purely “accidental”—as a result of his careless dancing. Instead an injured Frodo rises to his feet, clutching his bleeding hand, and wrestles with Gollum; during this fight both fall over the edge into the chasm of fire. Frodo (with the help of Sam) is able to hold onto the rock face and climb out; Gollum, however, is not and plunges into the fire, carrying the Ring with him just as he does in the book.

Though it isn’t clear who was initially responsible for suggesting this change, Peter Jackson has described his concerns that the scene as written in the book would be “a major disappointment” in the “dramatic context” of film:

We felt that audiences – a lot of people haven’t read the book, of course – would feel very let down and would actually judge Frodo badly for just sitting there watching as the ring got accidentally destroyed. (…)

They’d feel that Frodo would have failed essentially in his quest, and it was an accident that stepped in. We had to be careful in the movie to keep Frodo from looking bad because of that.

qtd. in Sandwell

In fact according to Jackson the first version of the scene that was shot included even more direct action on Frodo’s part:

When we originally shot the scene, Gollum bit off Frodo’s finger and Frodo pushed Gollum off the ledge into the fires below. It was straight-out murder, but at the time we were okay with it because we felt everyone wanted Frodo to kill Gollum.

ibid

Jackson apparently told Elijah Wood to play his attack as it appears in the final film ambiguously so that the viewer is left to wonder what Frodo would have done if he had succeeded in reclaiming the Ring from Gollum (Sandwell), thus maintaining the plausibility of Frodo’s “active role” in the Ring’s destruction.

Jackson is not the only person to have considered different and more “heroic” endings to this scene. Tolkien, himself, in earlier drafts of the scene, explored a very similar scenario to the one that appears in Jackson’s film. In The History of Middle-earth volumes VI—IX, Christopher Tolkien presents a number of his father’s early drafts of The Lord of the Rings, including outlines of the climactic scene. In an outline likely dating to 1939 and appearing in the ninth volume, Sauron Defeated, Tolkien writes: “At that moment Gollum — who had seemed to reform and had guided them by secret ways through Mordor — comes up and treacherously tries to take the Ring. They wrestle and Gollum takes Ring and falls into Crack” (3). According to Christopher it is clear that as early as 1940 Tolkien knew that “when Frodo…came to the Crack of Doom he would be unable to cast away the Ring, and that Gollum would take it and fall into the chasm. But how did he fall?” (37).

As Christopher suggests, while his father may have known from early on that the Ring would only fall into the fire along with Gollum, he seems to have been uncertain of the cause of Gollum’s fall. As his work on The Lord of the Rings continued over the decade and a half, Tolkien considered his options, pondering heavily Sam’s involvement—by turns Sam hurls himself into Gollum throwing them both into the fire (4), wrestles with Gollum and then throws him into the fire (4), sneaks up on Gollum while Gollum is dancing with glee and pushes him into the fire (5)—and even the possibility of Gollum jumping into the fire intentionally in a kind of ritual suicide meant to keep the Ring from anyone else. Yet Tolkien eventually ended up back where he started: simply that Gollum falls—no push, no shove, no wrestling. Indeed, according to Christopher the primary draft of the chapter “Mount Doom” (that is, its contents first put in prose and not in outline) is both complete and only differs from the published version in very minor ways:

It is remarkable in that the primary drafting constitutes a completed text, with scarcely anything in the way of preparatory sketching of individual passages, and while the text is rough and full of corrections made at the time of composition it is legible almost throughout; moreover many passages underwent only the most minor changes later. It is possible that some more primitive material has disappeared, but it seems to be far more probable that the long thought which my father had given to the ascent of Mount Doom and the destruction of the Ring enabled him, when at last he came to write it, to achieve it more quickly and surely than almost any earlier chapter in The Lord of the Rings.

37

As with many aspects of the novel, Tolkien’s choices here were the result of long and careful consideration. But did Tolkien view the destruction of the Ring as “accidental?” Perhaps we should return to those letters and let Tolkien describe the forces in action in the scene himself.

The Supreme Value and Efficacy of Pity

The following are excerpts from four of Tolkien’s letters published in The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien that mention Frodo’s failure and the forces that lead to the completion of the quest in his stead:

[Frodo] (and the Cause) were saved – by Mercy: by the supreme value and efficacy of Pity and forgiveness of injury. […] I did not ‘arrange’ the deliverance in this case: it again follows the logic of the story.

251

But at this point the ‘salvation’ of the world and Frodo’s own ‘salvation’ is achieved by his previous pity and forgiveness of injury. At any point any prudent person would have told Frodo that Gollum would certainly betray him, and could rob him in the end. To ‘pity’ him, to forbear to kill him, was a piece of folly, or a mystical belief in the ultimate value-in-itself of pity and generosity even if disastrous in the world of time. He did rob him and injure him in the end – but by a ‘grace’, that last betrayal was at a precise juncture when the final evil deed was the most beneficial thing any one cd. have done for Frodo! By a situation created by his ‘forgiveness’, he was saved himself, and relieved of his burden.

234

In this case the cause (not the ‘hero’) was triumphant, because by the exercise of pity, mercy, and forgiveness of injury, a situation was produced in which all was redressed and disaster averted.

252

Frodo had done what he could and spent himself completely (as an instrument of Providence) and had produced a situation in which the object of his quest could be achieved. His humility (with which he began) and his sufferings were justly rewarded by the highest honour; and his exercise of patience and mercy towards Gollum gained him Mercy: his failure was redressed.

325

Two things here are very obvious: firstly that Tolkien places responsibility for the completion of the quest on Frodo’s choice to extend pity to Gollum, and secondly that he describes the action of the climactic scene in consistently passive ways.

Pity is an idea that is addressed several times in The Lord of the Rings; its first appearance comes in chapter two of Book I, only moments before Frodo tries and fails to throw the Ring in the fireplace. Conversing with Gandalf about the likelihood that Gollum has exposed the names “Baggins” and “Shire” to Sauron, putting Frodo and all he loves in danger, Frodo exclaims that it was a pity that Bilbo did not kill Gollum during their encounter in The Hobbit. Gandalf, however, sees things differently:

Pity? It was Pity that stayed [Bilbo’s] hand. Pity, and Mercy: not to strike without need. And he has been well rewarded, Frodo. Be sure that he took so little hurt from the evil, and escaped in the end, because he began his ownership of the Ring so. With Pity.

59

Two things here are very obvious: firstly that Tolkien places responsibility for the completion of the quest on Frodo’s choice to extend pity to Gollum, and secondly that he describes the action of the climactic scene in consistently passive ways.

Our knowledge of Gandalf’s true nature is limited in The Lord of the Rings; it is only in The Silmarillion that we learn he is a maiar who has studied under Nienna, the vala of pity, mercy, compassion, and sorrow. The “supreme value and efficacy of pity and mercy” is likely something Gandalf knows quite a bit about, and he impresses upon Frodo its importance early on. It’s a lesson Frodo will have learned by the time he first meets Gollum; by that point he, too, will have suffered under the strain of the Ring, and will have come to identify with Gollum’s own tortured experience, finding him easy to pity at last. His pity for Gollum will prevent him from killing Gollum during their first meeting and many times afterwards. In fact, Gollum’s survival and presence at the climax is the result of a long string of acts ruled by pity. First is Bilbo’s pity that spares Gollum when Bilbo chooses not to kill him during his escape from the goblin tunnels in the pages of The Hobbit6. Next is an act of kindness (almost certainly engendered by pity) by the Elves of Mirkwood from whose custody Gollum escapes; this act of kindness leads to a planned ambush by orcs and the death of several elvish guards, but it also sets Gollum free to track Frodo and the Ring. Frodo’s continuous acts of pity will follow, as he refuses to kill Gollum despite recognizing Gollum is untrustworthy and likely to endanger the quest. Frodo will even plead with Faramir to spare Gollum’s life, despite the fact that Faramir, like Frodo, knows Gollum cannot be trusted. Lastly it is Sam (whose own bungled treatment of Gollum likely prevented Gollum’s full repentance) who will finally feel pity for Gollum: having at last experienced the weight of the Ring, himself, he refuses to kill Gollum on the slopes of Mount Doom just before the climactic scene.

These acts, as Tolkien says, are folly. No reasonable person would decide that the most prudent course of action is to spare Gollum’s life, especially not once Frodo and Sam have entered Mordor and have the Cracks of Doom in sight. And yet it is clear that without these continuous offerings of pity, grace, and mercy the quest would have failed. Frodo would have claimed the Ring. Sauron would have found him and taken it. The armies of the West would have been crushed, and Sauron’s dominion over Middle-earth would have been final. Gollum’s actions in the Cracks of Doom are ignoble, no doubt—they are driven by lust and total corruption—but they nonetheless inadvertently bring about the Ring’s destruction and the “salvation of the Cause.”

Abnegation and Plain Hobbit-sense

Frodo and Sam’s choices, both as they relate to Gollum and to the Ring, also express an incredible humility and awareness of their position relative to the enormity of the rest of the world. As Gandalf says during chapter two’s pity speech: “Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgement. For even the very wise cannot see all ends” (59).

Douglas Blount in his paper, “Uberhobbits: Tolkien, Nietzsche, And The Will To Power” describes those characteristics which Tolkien most closely identifies with heroism and moral authority: strength, according to Tolkien, manifests itself most clearly not in the exercise of power but rather in the willingness to give it up. “The greatest examples of the action of the spirit and of reason,” Blount tells us, “are in abnegation” (98).

Tolkien is clear that in this sense Frodo’s failure was not a moral one, as he had been pushed beyond his capacity and had maintained his moral integrity up until that moment—which, to go back to the discussion of Gollum being cursed, further undermines the idea that Frodo at any point actively used the Ring to curse or compel Gollum to his death.

It could be argued that hobbits, perhaps more than any of the “races” in Tolkien’s Middle-earth, reflect the virtues of humility and the abnegation of authority which is not theirs to claim. They are simple people who, on the whole, want to be left alone and do not seek domination of either people or of nature. And while their ignorance and small-mindedness are not traits to be looked up to (and everyone from Tolkien to Frodo to Gandalf does fault them for this), I would argue that they, as a group, represent the closest thing in the novel (outside of Tom Bombadil) to the antithesis of Sauron and the Ring.

Though Frodo does fail the final test, Tolkien assures us that it was a test outside Frodo’s (and indeed any person’s) capability to pass. In the heart of Sauron’s domain, at the fire where the Ring was forged, where all other powers were dimmed, no incarnate creature could have brought themselves to destroy the Ring. Tolkien is clear that in this sense Frodo’s failure was not a moral one, as he had been pushed beyond his capacity and had maintained his moral integrity up until that moment—which, to go back to the discussion of Gollum being cursed, further undermines the idea that Frodo at any point actively used the Ring to curse or compel Gollum to his death. Added together, these themes of pity and humility are part of why I would argue some of the changes made in Jackson’s adaptation of The Return of the King obscure some of the most important themes in The Lord of the Rings—in their effort to add additional dramatic tension or to give Frodo the appearance of more agency, they repeatedly dilute either Frodo’s sensible nature or the chain of pity that runs through the story7.

The compassion and mercy that Frodo shows to Gollum only maintains its thematic power if Frodo remains aware of how dangerous Gollum actually is. A Frodo who can be so easily tricked into believing Gollum over Sam—to the point that he would actually tell Sam to leave him—is no longer keeping Gollum around despite knowing he is untrustworthy. Hence, Frodo’s actions regarding Gollum are no longer acts inspired by pity of him.

Two of the film’s choices stand out in particular: a significantly altered scene while the heroes are climbing the Endless Stair in which Gollum tricks Frodo into believing Sam has turned against him leading Frodo to send Sam away, and the climax when Gollum falls into the fire as a result of struggling with Frodo over the Ring. The former, I would argue, works most strongly against both of the two important themes we have been examining in this section: pity and humility (or “plain hobbit sense”). Frodo’s “plain hobbit sense” is called into question here by his ability to be deceived so easily (in a moment which, as written, I would also argue is simply dramatically unbelievable.) More importantly, his deception in this moment interrupts the important chain of mercy and pity that is responsible for leading to the Ring’s destruction. The compassion and mercy that Frodo shows to Gollum only maintains its thematic power if Frodo remains aware of how dangerous Gollum actually is. A Frodo who can be so easily tricked into believing Gollum over Sam—to the point that he would actually tell Sam to leave him—is no longer keeping Gollum around despite knowing he is untrustworthy. Hence, Frodo’s actions regarding Gollum are no longer acts inspired by pity of him. Additionally, the reworking of the final confrontation at the Cracks of Doom, which places far more agency (albeit agency born of desire and rage rather than righteousness) on Frodo in the destruction of the Ring, muddies the still waters of the moment and reveals a lack of trust in the power and virtue of Frodo’s choices and actions prior to the moment, the choices and actions that Tolkien very explicitly tells us are responsible for the Ring’s destruction.

Now it’s time to bring these threads back together and explain why it is that Eru didn’t trip Gollum—why it is deeply important to the thematic and dramatic unity of The Lord of the Rings and Tolkien’s wider Legendarium that Gollum’s fall was not the result of a singular, direct, and unilateral intervention by Eru.

Part 4: Re-weaving The Tapestry

Threads of Fate

Peter Jackson was not wrong to be concerned that the implication (true or not) that the Ring was destroyed by accident would not sit well with some portion of his viewers. We yearn for some sense or meaning in the apparent chaos and happenstance of life; that storytelling exists at all may be sufficient evidence of this. Yet it is also true that we shrink in terror at the idea that our actions are not our own, that fate has us in a deterministic grasp. It is such a deterministic force that Plato in his Timaeus called ananke or “material necessity,” a force innate to matter which even his demiurgic God could not overcome.

Perhaps we might say that in Middle-earth when you choose, you are set on a course to your “doom.”

The characters in The Lord of the Rings seem interested in and aware of some form of mysterious order at work in the world. “Chance,” “luck,” and “happenstance” are repeatedly invoked in the text and often with a wink and a smile: whether it be in Bilbo’s “chance” encounter with the Ring just before the Necromancer is driven from Dol Guldur, “if chance it was” (250), Gandalf’s “chance” meeting with Thorin in Bree which leads to the events of The Hobbit, the “chance” encounter of the three traveling hobbits with Gildor’s elves in the Shire at just such a moment as to save the hobbits from the Black Riders, Tom Bombadil’s fortuitous and life-saving “chance” encounter with the same hobbits in the Old Forest, their “lucky” meeting with Strider in Bree, Boromir and Legolas’s “fortuitous” arrival to Rivendell at just the right time, or the “good fortune” of Gollum’s faulty footing. Yet, amid all this talk of fate and chance and luck we are given constant references to the fate-altering power of free will.

Choice absolutely does have a real effect on the world of Tolkien’s Middle-earth. Bilbo’s choice to extend pity to Gollum may “rule the fate of many” (59); Frodo realizes that he is “free to choose” (401) on the seat of Amon Hen; Faramir chooses not to follow the summons to Rivendell he hears in his dreams, leaving his brother Boromir to do so instead; most importantly, Frodo’s acts of pity enable the destruction of the Ring. This is no deterministic universe. In Middle-earth free will is absolutely real. So how can forces like “fate” and “choice” interact in a coherent way?

In her paper “Providence, Fate, and Chance: Boethian Philosophy in The Lord of the Rings” Kathleen E. Dubs recalls the words of Galadriel in Lothlorien after she has refused Frodo’s offer of the Ring:

They stood for a long while in silence. At length the Lady spoke again. ‘Let us return!’ she said. ‘In the morning you must depart, for now we have chosen, and the tides of fate are flowing.’” These ideas (free will and fate) are not incompatible if we view them in Boethian terms, for free will operates within the order of the universe, fate being merely the earthly manifestation of that order. And here we can see more clearly than before that free will sets that order in motion; Frodo’s and the Lady’s choices have determined the direction of that order, have set the tides flowing. It has not worked in the reverse direction. For ‘determinism’ to be applicable here, it would have to be defined anew.

40

Perhaps we might say that in Middle-earth when you choose, you are set on a course to your “doom.” These threads of fate, chosen and redirected by acts of free will, are heading towards something, some destination, some “doom,” and if you’ve been paying attention at all, you’ve likely noticed “doom” appearing a lot among these last several thousand words. It is surely no coincidence that the geographical goal of the quest—the setting for the climax of the action of the plot—is a place called The Cracks of Doom inside a mountain called Mount Doom over a magma pool called The Fire of Doom. It is here that many choices shall finally join together to “produce the situation” that ultimately allows the threat of Sauron to be overcome.

All Rivers Lead to Doom

Perhaps we can also conclude that the climax of The Lord of the Rings is described in passive terms by Tolkien because we are meant to view it as the setting of the revelation and working-out of a long-developing pattern, the outcome of which was clear all along. Tolkien says he “did not ‘arrange’ the deliverance in this case: it again follows the logic of the story” (Letters 251) and that “following the logic of the plot, it was clearly inevitable, as an event” (252).

The actions that take place when Frodo, Sam, and Gollum finally meet their “Doom” are merely the last in a long row of dominoes: most of the necessary actions that would lead to the overthrow of Sauron are in the past, and most of the consequential choices have already been made. We could speculate about where that line of dominoes started. A reasonable place to point to is the moment when Bilbo puts his hand on the Ring “blindly in the dark” (Tolkien, Lord of the Rings 55). However, we could also push it back further to Gandalf’s meeting with Thorin in Bree, or even further still: there’s a lot of “setting up” that Sauron does to himself. The choice to partly incarnate himself in a destructible object made him far more vulnerable, especially as it is an object that engenders in people such overpowering lust for it that they’d do something as unwise as dancing on the edge of a precipice above boiling magma.

As we can see, an important part of this pattern is evil’s propensity towards creating the circumstances of its own self-destruction, a theme so important that Tolkien includes it in his Legendarium’s creation myth. In “Ainulindale,” the first chapter of The Silmarillion, the Ainur are asked to compose and perform a Great Music together, improvising on Themes supplied by Eru. This Music will later become a blueprint of sorts for the universe. When Melkor, Tolkien’s analog to the Christian Lucifer, attempts to disrupt the Music by overpowering the other Ainur with his own repetitive and loud improvisations, Eru admonishes him and warns him that for all he tries to disrupt the Music and make it solely his own, his Discord shall ultimately work against him: “For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined” (17).

Gandalf’s proverb “oft Evil will shall evil mar” (Tolkien, Lord of the Rings 594) expresses a reality that is part of the metaphysical foundation of Tolkien’s Secondary World. It is, therefore, metaphysically and thematically appropriate that Gollum’s lust for the Ring and glee at its return leads to his literal fall. The necessary conscious act of good intent—throwing the Ring in the Fire—was one no one was capable of. As Paul Kocher explains in his early piece of literary criticism of Tolkien’s work, Master of Middle-earth, “The irony of evil is consummated by its doing the good which good could not do” (45).

The sudden revelation of a salvific pattern—created via the weaving together of a fate derived from choices both good and bad—at the moment when all hope seems lost, represents perhaps the perfected mode of eucatastrophe.

The sudden revelation of a salvific pattern—created via the weaving together of a fate derived from choices both good and bad—at the moment when all hope seems lost, represents perhaps the perfected mode of eucatastrophe. “Eucatastrophe” is a term Tolkien coined to describe “the happy turn” in fairy-stories (as he defines them), and it first appears in his essay, appropriately titled, On Fairy-stories. On Fairy-stories was written during the early years of Tolkien’s work on The Lord of the Rings and may be considered the conceptual background to the kind of narrative story-telling at work in his epic (Tolkien On Fairy-stories 15). In his description of eucatastrophe Tolkien says “[Eucatastrophe] depends on the whole story which is the setting of the turn, and yet it reflects a glory backwards” (76). This glory is the sudden realization, whether in the mind of the reader or the characters, that those events which had seemed to be chance or luck—especially bad luck—when experienced within the flow of the story, have in fact worked together for their deliverance.

In light of the above, I would argue that the “Eru tripping” interpretation contradicts both the dramatic intention of the scene and the very notion of this “backwards reflecting” eucatastrophe by adding a singular, direct, and unilateral cause for the Ring’s destruction in the very moment before this destruction happens—a cause which, because it is performed directly by Eru in the manner of a miracle, needs have no regard to the long line of causes which precedes it. This same undermining of dramatic intention applies to the interpretation that claims a curse tripped Gollum. Would a curse need a long line of causes behind it to function? In both cases, these other causes are superseded and become unnecessary. Additionally, the passive approach sounds much more like using Discord itself to bring the Music back into accord with the Theme. But if Gollum’s fall is passive in this sense—the end result of many, many choices woven together into fate—then what does Tolkien mean by his comments about the “Writer of the Story?”

Perpetual Production

Just because the cause of Gollum’s fall is passive, just because Eru didn’t “trip” Gollum, does not mean his fall is truly “accidental,” because Eä—the universe and the entire playing out of the events within in it—is conceived, in-text, as a Story or Drama8. In his essay “Over the Chasm of Fire,” Stanford Caldecott notes that Sam’s comments after the climax of The Lord of the Rings have a much more literal meaning than Sam may even realize: “‘What a tale we have been in, Mr Frodo, haven’t we? I wish I could hear it told!’ (…) Sam has bridged the gap, and seen their own lives as part of a great tale full of wonder and meaning, that stretches from the beginning of time to its mysterious end” (32).

When Tolkien uses the words “Writer of the Story” he makes it clear he is not referring to himself (though the humorous comparison may well be on his mind9). In this aspect I think the “tripped” interpretation is absolutely correct: “the Writer of the Story” is a reference to Eru. My disagreement comes in what it means for Eru to “take over” the story.

The world of Middle-earth is a pre-Christian one, far more like the fading pagan backdrop of the world in Beowulf than the Christian allegory of Narnia, but Tolkien was also quite devoutly Catholic, his faith a potent and foundational part of his worldview (though it should be noted that to say this is not the same as to say it was the entirety of his worldview or that he was always of one mind on matters of faith and theology). Just as the characters in The Lord of the Rings appear to be aware of some sense of fate at work in the world, many also attribute to that fate a kind of rational intention outside the bounds of mere determinism. As Gandalf says to Frodo regarding Bilbo’s discovery of the Ring: “Behind that there was something else at work, beyond any design of the Ring-maker. I can put it no plainer than by saying that Bilbo was meant to find the Ring, and not by its maker” (56). This guiding or shepherding—but not controlling—of people and events is Providence. Tolkien repeatedly refers to Providence when describing the events of the climax of The Lord of the Rings.

No account is here taken of ‘grace’ or the enhancement of our powers as instruments of Providence. Frodo was given ‘grace’: first to answer the call (…) and in his endurance of fear and suffering. But grace is not infinite, and for the most part seems in the Divine economy limited to what is sufficient for the accomplishment of the task appointed to one instrument in a pattern of circumstances and other instruments.

454

Frodo had done what he could and spent himself completely (as an instrument of Providence) and had produced a situation in which the object of his quest could be achieved.

325

What form Providence takes within Eä is less clear. What or who was “guided” such that Bilbo found the Ring? And in what way? Did Eru “cause” Gandalf to reach Bree at just such a time as to meet Thorin, setting in motion Gandalf’s hunt for a burglar? Or did he “cause” the same for Thorin? Did he make the floor of the goblin tunnels below the mountain crumble under Bilbo, landing him directly in the Ring’s path? Or did he guide Bilbo’s hand “blindly in the dark” until it brushed against cold metal? We cannot say with any certainty. These providential interventions are such that, if they do in fact exist, we do not or cannot see them. We cannot verify them, and in the moment they seem easily attributable to a variety of other causes or merely to “accident.” Unlike The Silmarillion’s explicitly stated and miraculous interventions—the awakening of the Elves or the Drowning of Numenor—we are never told what these providential interventions are or when they take place. We can only, like Gandalf, suspect them, in the way a particularly sharp movie goer might suspect a certain event or turn of phrase was an instance of foreshadowing: we recognize them as making “story-sense.” Thomas Hibbs describes the Eä we are presented with in The Lord of the Rings as a universe in which “individuals can have confidence that there is an order for them to discern and tasks for them to fulfill, since a providential world is one in which human history has the structure of a plot, an intelligible dramatic unity” (178).

These providential interventions are such that, if they do in fact exist, we do not or cannot see them. We cannot verify them, and in the moment they seem easily attributable to a variety of other causes or merely to “accident.”

Tolkien even wrote an in-universe debate about the very topic of the nature of Eru’s involvement (or lack thereof) in the events of Arda where he makes the nature of Eä as Drama explicit and diegetic. Called “Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth” and appearing in Morgoth’s Ring (the tenth volume of The History of Middle-earth series) this debate between the elven king Finrod and the wise woman Andreth centers around what Tolkien calls “Oinekarmë Eruo (The One’s perpetual production), which might be rendered by ‘God’s management of the Drama’” (329). While nothing in The Lord of the Rings approaches the explicit and diegetic nature of this debate, the early exchange between Gandalf and Frodo mentioned above—Gandalf’s voicing of his suspicion that Bilbo was meant to find the Ring—reproduces to some degree the same opposition of viewpoints. Gandalf ends with the statement “and that may be an encouraging thought,” to which Frodo replies “it is not” (56). Frodo shares Andreth’s cynicism and does not find in the idea the comfort that Gandalf does.10

Providence (for Tolkien) is not Miracle

As we have already discussed, some of Eru’s involvements in the Story—the awakening of Elves and Men and the Downfall of Numenor—appear to describe a mode of involvement that is singular, direct, and unilateral and which we might define as “miracle.” In his essay “Conflict and Convergence on Fundamental Matters in C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien,” Ralph Wood notes the attributes of Tolkien’s idea of miracles:

But for Tolkien as not for Lewis, miracles are unique acts of God; they are not special demonstrations of what God always does through the operations of nature. There is, in fact, an implicit Thomism at work in Tolkien’s understanding of miracles. As Brian Davies observes, Aquinas “thinks that miracles come about by virtue of the creative activity of God and nothing else. The whole point about them is that nothing subject to God’s providence, i.e. no cause other than God (no secondary cause), is at work in their occurrence” This is not to say that God does violence to the created order, or that he “intervenes” to disrupt its natural processes. On the contrary, St. Thomas insists that God is totally present to every existing thing, so that all events are always the effect of God’s will. Yet miracles are not worked through secondary causes, not even through their divine compression, as Lewis argues: they are brought about by God alone.

325

This description of miracles as those events which work through no secondary causes is echoed by Purtill in J.R.R. Tolkien: Myth, Morality, and Religion:

By definition miracles are an intervention from outside of ordinary life that cannot be expected, counted on, or prepared for. Unless you take on the impossible task of writing a story from God’s point of view, there is no way in which you can show a miracle as an event following from the characters and circumstances of the story….

154

A “miracle” then is not an event that we could say “follows the logic of the plot,” as Tolkien describes the events of the climax of The Lord of the Rings. For Tolkien, miracles are fundamentally unlike the actions of Providence, which holds free choice among rational creatures as sacrosanct and seems to work within Eä almost as an undetectable force of nature. Christin Ivey uses the image of an “underlying current” to describe this force:

With Providence’s active involvement in guiding Frodo’s free will, Tolkien presents Providence not as stoic ‘clock-work God’ but as an underlying current, flowing together the free will choices that determine the earthy derived plan of fate; ultimately leading into compliance with the thematically cohesive divine design. Helen Lasseter concludes: ‘While guiding all events and actions to an ultimate good, Providence never denies creatures their freedom… [Tolkien] shows that the person is integral to a providential world order; yet the person’s inherent limitations, exposed through personal failure and defeat, reveal the constant presence of a higher and greater authority within the world.’

196

For Eru to use a miracle rather than the actions of providence it must be necessary to use a miracle rather than the actions of providence. If Gollum was so near to falling, why not let it be that he fell? What does Eru tripping Gollum say that isn’t better said by allowing Gollum’s own glee to destroy the Ring? Gollum’s madness and lust is a better cause dramatically, thematically, and theologically. And if it were as simple as tripping someone into the Fire, why didn’t Eru do so with Sauron just after he made the Ring? There is no reason for it to happen now rather than then. Alternatively, he could have torn the Ring off Frodo’s finger. He could have prevented Sauron’s fall into evil entirely. Or he could have prevented Melkor from singing at the very start, ending evil before it began. But he doesn’t.

The events in the Cracks of Doom constitute a providential eucatastrophe, not a miraculous deus ex machina. Eru does not “enter” the story to intervene at the last moment—Eru has been present all along.

The events in the Cracks of Doom constitute a providential eucatastrophe, not a miraculous deus ex machina. Eru does not “enter” the story to intervene at the last moment—Eru has been present all along. This is consonant with what we know of how Eru deals with concentrated incarnate evils in the world. Eru does not often jump in with miracles, and when he does it is never to stop atrocities from happening. The destruction of Numenor, for example, does not kill Sauron and does not prevent all the harm the Numenoreans have already done.11 Eru leaves the stopping of evil to others (and to evil itself).

Providence is not a “change of plan.” Providence is the plan. It is not Eru working alone. It is not “miracle.” Eru may not have tripped Gollum, but he gave Gollum, Frodo, Sam and every other rational being opportunities to make choices which, in concert, produced a situation that led to the Ring’s destruction.

Rending the Web of Story

There is one last important point. The universe of Tolkien’s Legendarium is a teleological one. Providence is leading towards… something, some meaningful end, though those who have never been outside of it are at an epistemological disadvantage when it comes to puzzling out what that end is. While Tolkien never completely formulated an entire eschatology for his Legendarium, he did note one important feature of what would come “after” Eä: a Second Music in which the Children of Eru (Elves and Men) would join the Ainur in song.

As scriptless actors in the Drama, the very choices of the Children of Eru are their art, their sub-creations, and that makes their very choices infinitely important.

This Music, like the first, is not merely ornamental, or a work in and of and for itself. Like the First Music it is a pattern, a blueprint of things to come, things that will be made Real, and it is a work that humanity will participate in. This hopeful view of eternity—one that is echoed in Tolkien’s allegorical short story “Leaf by Niggle” when the protagonist sees his own creation given material reality after his death—is one that Tolkien appeared (at least at times) to believe was active in the real world. As Tolkien says at the end of On Fairy-stories: “All tales may come true…” (79).

Most importantly, however, is this: this communal art making shared among all the human beings in the world is not something that happens only at The End. The Children of Eru are fundamentally sub-creative beings, art-makers, who are made precisely in order to express the infinite variety of Eru’s infinite Being through their own unique creations. These creations are not limited to what we would traditionally call “art works.” As scriptless actors in the Drama, the very choices of the Children of Eru are their art, their sub-creations, and that makes their very choices infinitely important. In The Flame Imperishable, Jonathan McIntosh thoroughly situates the metaphysical underpinnings of Tolkien’s Secondary World in the metaphysics of Thomas Aquinas, including the notion that all human action represents a kind of shared creative activity with the Creator:

In our acts of sub-creation, God has chosen to create through us, as it were, not in the sense that we are made the intermediate agents or instruments of his creation, but in the sense of our sub-creative activity becoming the locus at which God carries on or continues his own work of creation. (…)

Human praxis, as it were, is a kind of human poesis, human doing a form of human making, inasmuch as every human action seeks to bring about an alternative state of affairs, and therefore to realize a “secondary world” or reality that is alternative to the one currently realized.

181

These choices, all adding up to join together as the threads of fate—and more importantly these choices made in fellowship—reflect the Music as it was meant to be: a pluralistic effort of infinite variety. The pity shown to Gollum, for instance, the salvific force which, while not functioning alone, is given special attention in Tolkien’s commentary, is not just pity, but many acts of pity by many different players: pity in fellowship.

The pity shown to Gollum, for instance, the salvific force which, while not functioning alone, is given special attention in Tolkien’s commentary, is not just pity, but many acts of pity by many different players: pity in fellowship.

So who was responsible for the Ring’s destruction?

In a very real sense, they all were. Everyone whose choices interlocked in order to produce the circumstances at work at the Cracks of Doom, even Sauron, even the Ring, itself, is responsible, to varying degrees, for the Ring’s destruction. It may not be out of line to include in this group even every rational being who had ever lived up to that point. Because that is how The Music, the blueprint of Providence, is meant to work.

The stories of Tolkien’s Legendarium are conceived as a kind of mythological history of our own world. Tolkien, in fact, introduces himself to us in the prologue to The Lord of the Rings not as author, but as translator of long lost documents recording the events of pre-history. Tolkien wants us to know that we are living in Eä in an Age long after the fall of Sauron and the fading of the Elves, that we are reading a story about a world that is itself a story—and that story happens to be our own. It’s story all the way down. Which means our choices are inviolable, too; Frodo’s agency is also our agency. The web of story is torn asunder, and suddenly we, like hobbits, are forces that shape the universe. It is our choice-making—our art-making!—that expresses the infinite variety of God just as much as Frodo’s does.

If we allow ourselves to step into Tolkien’s Secondary World we may stop for a moment and take him seriously: one day we will sing the Second Music, but even here and even now we are all—already—con-creators with The One.

And that (may be) an encouraging thought.

Notes

- A fact that I would argue should be of no great surprise since the Ring can be understood as a secondary incarnation of Sauron. ↩︎

- It is not strictly true that wearing the Ring alone is sufficient to expose someone to Sauron’s gaze: Sam wears the Ring while rescuing Frodo from Cirith Ungol, but Sauron does not see him. Yet, there is a sense that the combination of how often a person uses the Ring, combined with proximity to Orodruin, their intentions when wearing the Ring, and whether they are part of some other “magical” process (such as on Amon Hen) increase the possibility that Sauron will “see” them. ↩︎

- A long post on the method and functioning of the Ring will have to be left for another day. Suffice it to say the distinctions between proximity to/bearing of/wearing of/and claiming the Ring are an interesting topic. ↩︎

- This, of course, assumes that in order to “curse” Frodo would need to use the Ring. As a hobbit unrelated to any particularly powerful bloodline (in the way Aragorn and Isildur were) it seems unlikely to me Frodo alone could curse Gollum in any real and binding way. ↩︎

- I suspect there may be some disagreement over whether “Osanwe-kenta,” a piece which dates to the late 1950s shortly after the publication of The Lord of the Rings, should be considered authoritative for interpreting the events of the novel. Since it was written not long after, in a time period in which Tolkien’s intent seemed to be to bring the greater mythology in line with The Lord of the Rings, and also since Tolkien seemed to view published works with some heightened level of authority, I believe it would have been written with the binding nature of The Lord of the Rings in mind. Whether texts outside The Lord of the Rings (and The Hobbit) should be used to aid in a reading of The Lord of the Rings is a valuable question, but since the inclusion of Letter 192 as an interpretive aid is presupposed in this essay, I see no reason not to consider other texts as well. ↩︎

- This choice of Bilbo’s did not appear in the first edition of The Hobbit: Tolkien altered the book to reflect the new, more powerful, and far more malevolent nature of the One Ring, and it is worth noting that he felt it important enough to include this act of pity in his alterations. ↩︎

- To be absolutely fair, Jackson wasn’t unaware of the pity issue, and states as much in the same interview. However, he presumably felt the theme wouldn’t be communicated sufficiently in the medium of film so as to override concerns about the audience’s reaction to Frodo’s passivity. ↩︎

- It should be noted that my intention here is not to explore the moral and ethical questions present in this interpretation of divine beings and their moral duty, or lack thereof, to intervene in the world for the sake of Good, including whether or not this is consonant with the operations of a loving creator, or produces a satisfying or comforting theology. Whether such a “way of things” is Good is its own worthy question (and has been debated for millennia). It may, however, also be a question for which there is no truly satisfying answer. ↩︎

- Tolkien is paralleling himself with the Other Writer when he says that he did not “arrange” the action. Perhaps he’s being cheeky: the Other Writer didn’t “arrange” the action either: it “follows the logic of the Other Writer’s story.” ↩︎

- In their debate Andreth is of the mind that Eru, if he exists, has little to do with his Children, since Men have no encounters with him or with his regents (the Valar) as the Elves claim they do. Finrod, on the other hand, argues not only for his continual presence but for the goodness of his plans and intentions, a perspective which Andreth, a mortal woman “doomed to die” points out is molded by Finrod’s privileged position as an immortal Elf. It is tempting to see Tolkien in this debate providing a fictional outlet for his own lifelong struggle with the reality of evil and death and the question of how this reality can coexist with a benevolent Creator—that is, his struggle with the Problem of Evil. One wonders if Tolkien is both Finrod and Andreth in this instance, just as one wonders if he is both Gandalf and Frodo. ↩︎

- Eru imposes to stop the armada not because they were evil, but because allowing Men access to Valinor was a catastrophic failure of their nature and future purpose. ↩︎

Works Cited

- “Involvement.” Eru Ilúvatar, One Wiki to Rule Them All, lotr.fandom.com/wiki/Eru_Ilúvatar. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

- Blount, Douglas K. “Uberhobbits: Tolkien, Nietzsche, And The Will To Power.” The Lord of the Rings and Philosophy: One Book to Rule Them All, edited by Gregory Bassham and Eric Bronson. Carus Publishing Company, 2003.

- Caldecott, Stratford. “Over the Chasm of Fire: Christian Heroism in the Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings.” Tolkien: A Celebration, edited by Joseph Pearce. London: Harper Collins, 1999.

- Dubs, Kathleen, “Providence, Fate, and Chance: Boethian Philosophy in The Lord of the Rings.” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 27, no. 1, 1981, pp. 34-42.

- Hibbs, Thomas. “Providence and Dramatic Unity in The Lord of the Rings.” The Lord of the Rings and Philosophy: One Book to Rule Them All, edited by Gregory Bassham and Eric Bronson. Carus Publishing Company, 2003.

- Ivey, Christin. “The Presence of Divine Providence in the Absence of ‘God’: The role of Providence, Fate, and Free Will in Tolkien’s Mythology.” The Corinthian, vol. 9, no. 1, 2008, pp. 189-99.

- Kocher, Paul. Master of Middle-earth. New York: Ballantine Books, 1978.

- McIntosh, Jonathan. The Flame Imperishable: Tolkien, St. Thomas, and the Metaphysics of Faerie. Kindle ed., Angelico Press, 2018.

- Meyer Sparks, Patricia. “Power and Meaning in The Lord of the Rings.” Understanding The Lord of the Rings: The Best of Tolkien Criticism, edited by Rose A. Zimbardo and Neil D. Isaacs. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004.

- Purtill, Richard. J.R.R. Tolkien: Myth, Morality, and Religion. Ignatius Press, 2003.

- Sandwell, Ian. “Lord of the Rings almost had a much darker ending.” Digital Spy, 4 Mar. 2021, http://www.digitalspy.com/movies/a31925985/lord-of-the-rings-ending-frodo-gollum/. Accessed 17 Sept. 2021.

- Tolkien, J. R. R.. “The Hunt for the Ring.” Unfinished Tales of Numenor and Middle-earth, edited by Christopher Tolkien, Annotated ed., Kindle ed., Mariner Books, 2012.

- —. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter, 1st ed., Kindle ed., Mariner Books, 2014.

- —. The Lord of the Rings: One Volume. 50th Anniversary ed., Kindle ed., Mariner Books, 2012.

- —. Morgoth’s Ring. Vol. 10 of The History of Middle-earth, edited by Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993.

- —. “Osanwe-kenta.” The Nature of Middle-earth, edited by Carl F. Hostetter. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021.

- —. The Peoples of Middle-earth. Vol. 12 of The History of Middle-earth, edited by Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996.

- —. Sauron Defeated. Vol. 9 of The History of Middle-earth, edited by Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1992.

- —. The Silmarillion. Edited by Christopher Tolkien, Reissue ed., Kindle ed., Mariner Books, 2012.

- —. Tolkien on Fairy-Stories. Edited by Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson. London: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2014.

- Wood, Ralph C.. “Conflict and Convergence on Fundamental Matters in C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.” Renascence, vol. 55, no. 4, 2003, pp. 315-38.

Leave a Reply